War crimes investigation proceeding against Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper?

Heinous Crimes, Latest news, World news Tuesday, February 8th, 2011

The ICC’s chief prosecutor, Luis Moreno Ocampo, is conducting a “preliminary examination” into human rights abuses committed in Afghanistan by Taliban and ISAF forces alike. And while the ICC has focused in recent years on prosecuting African despots, Mr. Ocampo said he will not back down from prosecuting Western governments that are not holding their officials accountable for their actions.

“I prosecute whoever is in my jurisdiction. I cannot allow that we are a court just for the Third World. If the First World commits crimes, they have to investigate. If they don’t, I shall investigate,” Mr. Ocampo said. “That’s the rule and we have one rule for everyone.”

According to the ICC, Canadian officials (mainly Stephen Harper and Peter MacKay) may be in breach of the Geneva Convention and have launched an official war crimes investigation.

Between 2006 and 2007, Richard Colvin, the second-highest-ranking Canadian diplomat in Kabul, sent 17 reports about torture to Ottawa. The reports, which were circulated widely within the departments of Foreign Affairs and National Defence, confirmed public warnings from international officials and journalists.

In March 2006, Louise Arbour, the then UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, reported that complaints of torture at the hands of Afghan officials were “common.”

In June 2006, the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission estimated that “about one in three prisoners handed over by Canadians are beaten or even tortured in local jails.”

In March 2007, the U.S. State Department reported that unconfirmed reports of torture were “numerous” in Afghanistan.

In April 2007, the Globe and Mail reported on “a litany of gruesome stories and a clear pattern of abuse by the Afghan authorities who work closely with Canadian troops.”

Yet the Canadian Government did next to nothing. In April 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper said that “Canadian military officials don’t send individuals off to be tortured.”

Colvin’s testimony directly contradicts the Prime Minister’s statement. He reports that all the transferred detainees were tortured and that this was widely know in Kandahar, including among Canadian soldiers and diplomats.

Colvin reports that the Red Cross tried unsuccessfully for three months to convey its concerns to the Canadian military about problems in the way Canada was reporting to the Red Cross when it transferred detainees to the Afghan authorities.

Colvin’s allegations emerged because he was called to testify before the Military Police Complaints Commission, a body—established after the Somalia Inquiry—which has been investigating detainee transfers at the request of Amnesty International and the BC Civil Liberties Association. The Harper government sought to block Colvin’s testimony before the MPCC, citing national security. The obstruction prompted the three Canadian opposition parties to call Colvin to testify before a Parliamentary committee.

The actual facts are still emerging, but all the elements of a war crime are present. The prohibition of torture ranks with the prohibitions of genocide and slavery as one of the most fundamental rules of international law. Torture—and complicity in torture—is a “grave breach” of the 1949 Geneva Conventions. If Canadian officials allowed detainees to be transferred to Afghan custody despite an apparent risk of torture, and chose not to take reasonable steps to protect them, they are as guilty of a war crime as the torturers themselves. They can be prosecuted in Canada under the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act. Or they could be hauled before the International Criminal Court. Canada has ratified the ICC’s statute, giving it jurisdiction over Canadians who commit war crimes anywhere. However, the International Criminal Court will not intervene if Canadian officials are willing and able to investigate and prosecute. As Stephen Harper has been uncooperative the ICC has proceeded to investigate minority Prime Minister Stephen Harper and other high ranking Canadian political officials including Defense Minister Peter MacKay for war crimes.

With the government refusing to start a public inquiry and the International Criminal Court having launched a “preliminary” investigation into the Afghan detainee issue, law experts say there is a very real chance Canadian officials could be charged with war crimes.

“International law is very clear,” said Mr. Dosanjh, a lawyer and former attorney general of British Columbia. “You need circumstantial evidence; you don’t need actual knowledge of any specific allegations, or actual knowledge of torture. There was substantial knowledge of torture in Afghan jails. Every kid on the ground knew that. All of the reports, national or international, knew that.”

University of Ottawa law professor Errol Mendes says Mr. Dosanjh was correct. The government’s oft-repeated line that there was no documented physical evidence of torture of Canadian-transferred detainees is a “detour,” he said, which ignores the actual requirements of the law: circumstantial evidence that a risk of torture existed.

Having ratified the Geneva Convention, Canada incorporated its principles into domestic law through the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act. Under this domestic law, Mr. Mendes said, the RCMP can investigate government officials.

Mr. Mendes said that for the “honour and dignity of Canada,” the government should call a public inquiry. Once the facts are out in public, he said, the RCMP could decide whether to charge officials, or whether the political consequences—for example, if a minister were to resign—were sufficient.

He added that jurisprudence holds that the responsibility for such transfers rests with those who authorized the transfer.”While the front line soldiers may have done the actual transfer, the culpability actually lies at the civilian command level: The ones who set the framework in place,” Mr. Mendes said.

However, since the Harper government refused to launch a Canadian investigation that can open it up to international judicial systems. The International Criminal Court considers itself a court of last resort, abiding the principle of “complemenarity.” This means the ICC can only exercise its jurisdiction where the home country of the suspect in question is unable or unwilling to prosecute. As Harper is unwilling to launch a Canadian investigation the ICC is now proceeding with it own.

Due to the failure of Canadian officials to impose a rigorous transfer agreement, Harper has wilfully been placing detainees at well-documented risk of torture, cruel treatment and outrages upon personal dignity. As such, Harper and MacKay have been committing war crimes…in circumstances that clearly fall within the Court’s jurisdiction.”

“There are substantial grounds to believe that when Canadian Forces transfer a prisoner into Afghan custody, torture or ill treatment will occur,” In doing so, Canada is in violation of its international human rights obligations.

“For a significant period of time, [officials] knew there was a substantial risk of torture, they knew how to prevent it, and they chose for a substantial period of time not to take preventative measures.”

This case is particularly serious because, rather than torture being abetted by a low-ranking soldier acting alone, complicity appears to go “all the way up the chain of command up to the defense minister, foreign minister and even to the prime minster of Canada.”

That’s what distinguishes this from standard war crimes cases. They’ve got the command responsibility, and that’s why the ICC prosecutor have initiate a formal investigation.

As Colvin himself explained: “If we disregard our core principles and values, we also lose our moral authority abroad. If we are complicit in the torture of Afghans in Kandahar, how can we credibly promote human rights in Tehran or Beijing?”

Even more seriously, the government’s indifference to torture may have created greater risks for Canadian soldiers. Insurgents who believe they will be tortured will fight to the death rather than surrender, placing Canadian soldiers at increased danger of harm. As a result, it is possible that one or more soldiers might have been killed as a result of the Canadian Government’s actions. Again, as Colvin cogently explained: “In my judgment, some of our actions in Kandahar, including complicity in torture, turned local people against us. Instead of winning hearts and minds, we caused Kandaharis to fear the foreigners. Canada’s detainee practices alienated us from the population and strengthened the insurgency.”

It’s time for Canadians to rally together. It’s time to insist that any war criminals be investigated and prosecuted, regardless of who they are.

Short URL: https://presscore.ca/news/?p=1167

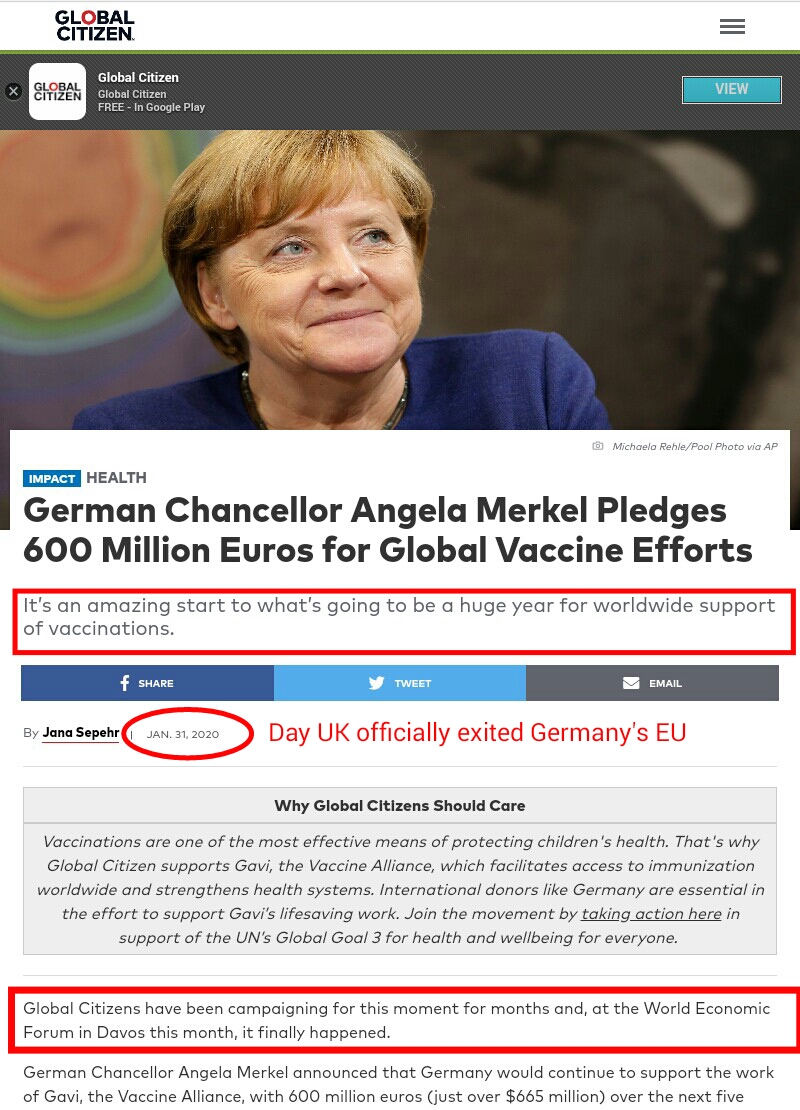

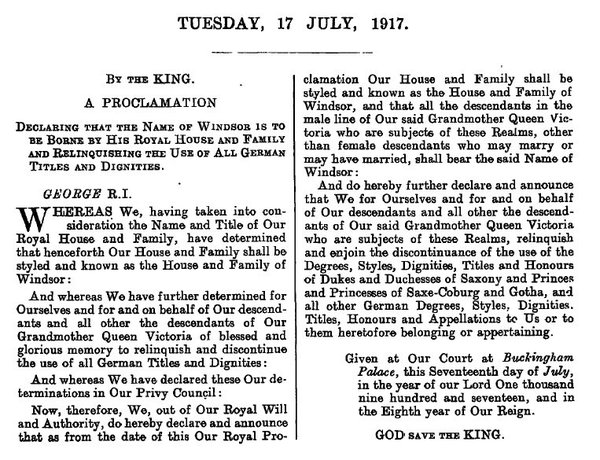

The Halifax International Security Forum was founded in 2009 as a propaganda program within the German Marshall Fund (founded June 5, 1972 by West German Chancellor Willy Brandt) by the Crown in Canada using Crown Corp ACOA & DND funds. The Halifax International Security Forum is a front that is used to recruit top US, UK and Canadian gov and military officials as double agents for Canada's WWI, WWII enemy and wage new Vatican Germany Cold War.

High Treason: s.46 (1) Every one commits high treason who, in Canada (c) assists an enemy at war with Canada, ..., whether or not a state of war exists". Every one who, in Canada assists Canada's enemies wage "piecemeal WWIII" Cold War by organizing, funding and participating in the Germany government politically and militarily benefitting / lead Halifax International Security Forum is committing high treason.

The Halifax International Security Forum was founded in 2009 as a propaganda program within the German Marshall Fund (founded June 5, 1972 by West German Chancellor Willy Brandt) by the Crown in Canada using Crown Corp ACOA & DND funds. The Halifax International Security Forum is a front that is used to recruit top US, UK and Canadian gov and military officials as double agents for Canada's WWI, WWII enemy and wage new Vatican Germany Cold War.

High Treason: s.46 (1) Every one commits high treason who, in Canada (c) assists an enemy at war with Canada, ..., whether or not a state of war exists". Every one who, in Canada assists Canada's enemies wage "piecemeal WWIII" Cold War by organizing, funding and participating in the Germany government politically and militarily benefitting / lead Halifax International Security Forum is committing high treason.

Please take a moment to sign a petition to

Please take a moment to sign a petition to

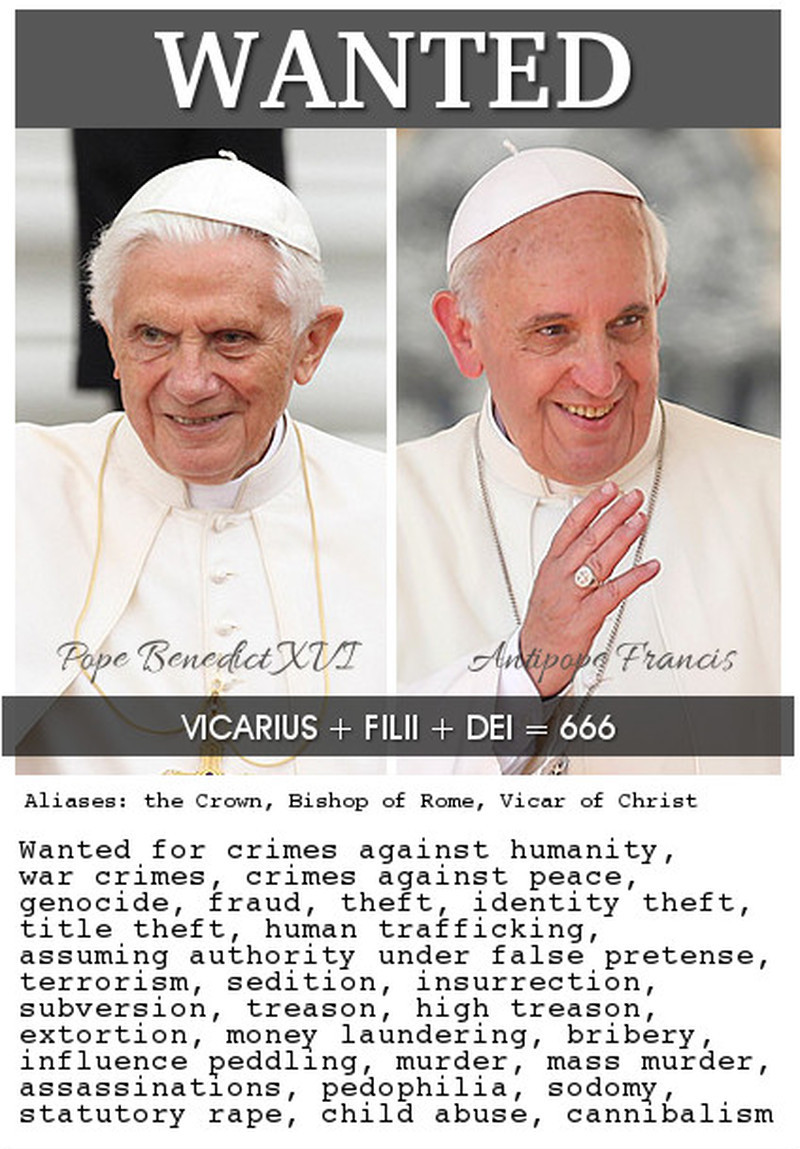

1917 Code of Canon Law, Canon 185 invalidates (voids) all papacies since October 26, 1958 due to the fact Cardinal Giuseppe Siri was elected Pope on the Third ballot on Oct 26 1958 but the new Pope Gregory XVII was illegally prevented from assuming the office. A Pope was elected on October 26, 1958. Thousands of people witnessed a new Pope being elected by seeing white smoke and millions were informed by Vatican radio broadcasts beginning at 6:00 PM Rome time on October 26, 1958. The papacy of Francis, Benedict, John Paul II, John Paul I, Paul VI, John XXIII and any and all of their respective doctrines, bulls, letter patents and the Second Vatican Council are all invalidated (having no force, binding power, or validity) by Canon 185 because the 1958 conclave of cardinals elected Cardinal Giuseppe Siri Pope on Oct 26 1958. Cardinal Giuseppe Siri accepted the papacy by taking the name Pope Gregory XVII but was illegally prevented from assuming his elected office.. According to Canon 185 Cardinal Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli illegally assumed the papacy 2 days later by fraud and grave fear, unjustly inflicted against Cardinal Giuseppe Siri who was lawfully elected Pope Gregory XVII. Because no Pope has been lawfully elected since October 26, 1958 the Holy See (la Santa Sede/Seat) remains vacant.

1917 Code of Canon Law, Canon 185 invalidates (voids) all papacies since October 26, 1958 due to the fact Cardinal Giuseppe Siri was elected Pope on the Third ballot on Oct 26 1958 but the new Pope Gregory XVII was illegally prevented from assuming the office. A Pope was elected on October 26, 1958. Thousands of people witnessed a new Pope being elected by seeing white smoke and millions were informed by Vatican radio broadcasts beginning at 6:00 PM Rome time on October 26, 1958. The papacy of Francis, Benedict, John Paul II, John Paul I, Paul VI, John XXIII and any and all of their respective doctrines, bulls, letter patents and the Second Vatican Council are all invalidated (having no force, binding power, or validity) by Canon 185 because the 1958 conclave of cardinals elected Cardinal Giuseppe Siri Pope on Oct 26 1958. Cardinal Giuseppe Siri accepted the papacy by taking the name Pope Gregory XVII but was illegally prevented from assuming his elected office.. According to Canon 185 Cardinal Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli illegally assumed the papacy 2 days later by fraud and grave fear, unjustly inflicted against Cardinal Giuseppe Siri who was lawfully elected Pope Gregory XVII. Because no Pope has been lawfully elected since October 26, 1958 the Holy See (la Santa Sede/Seat) remains vacant.

Hold the Crown (alias for temporal authority of the reigning Pope), the Crown appointed Governor General of Canada David Lloyd Johnston, the Crown's Prime Minister (servant) Stephen Joseph Harper, the Crown's Minister of Justice and Attorney General Peter Gordon MacKay and the Crown's traitorous military RCMP force, accountable for their crimes of treason and high treason against Canada and acts preparatory thereto. The indictment charges that they, on and thereafter the 22nd day of October in the year 2014, at Parliament in the City of Ottawa in the Region of Ontario did, use force and violence, via the staged false flag Exercise Determined Dragon 14, for the purpose of overthrowing and besieging the government of Canada contrary to Section 46 of the Criminal Code. In a society governed by the rule of law, the government and its officials and agents are subject to and held accountable under the law. Sign the online

Hold the Crown (alias for temporal authority of the reigning Pope), the Crown appointed Governor General of Canada David Lloyd Johnston, the Crown's Prime Minister (servant) Stephen Joseph Harper, the Crown's Minister of Justice and Attorney General Peter Gordon MacKay and the Crown's traitorous military RCMP force, accountable for their crimes of treason and high treason against Canada and acts preparatory thereto. The indictment charges that they, on and thereafter the 22nd day of October in the year 2014, at Parliament in the City of Ottawa in the Region of Ontario did, use force and violence, via the staged false flag Exercise Determined Dragon 14, for the purpose of overthrowing and besieging the government of Canada contrary to Section 46 of the Criminal Code. In a society governed by the rule of law, the government and its officials and agents are subject to and held accountable under the law. Sign the online  Two of the most obvious signs of a dictatorship in Canada is traitorous Stephen Harper flying around in a "military aircraft" and using Canadian Special Forces "military" personnel from JTF2 and personnel from the Crown's traitorous martial law "military" RCMP force as his personal bodyguards.

Two of the most obvious signs of a dictatorship in Canada is traitorous Stephen Harper flying around in a "military aircraft" and using Canadian Special Forces "military" personnel from JTF2 and personnel from the Crown's traitorous martial law "military" RCMP force as his personal bodyguards.

Harper actually shut down Parliament to avoid tough questions about allegations that prisoners handed over by Canada to Afghan authorities were later tortured. In an act of obstructing justice Harper had the Governor General prorogue government. While a parliament is prorogued, between two legislative sessions, the legislature is still constituted but all orders of the body – bills, motions, etc. are expunged (non-existent). When Parliament reconvenes, those bills will have to start again from scratch.

Harper’s move was purely for self-interest. He faced grilling by parliamentary committees over whether he misled the House of Commons in denying knowledge that detainees handed over to the local authorities by Canadian troops in Afghanistan were being tortured. Prorogation meant that such committees—which carry out the essential democratic task of scrutinizing government—will have to be formed anew. With such a long delay Harper was banking on the Canadian public forgetting about his complicity in committing war crimes. Prorogation was implemented by Harper to cover-up his war crimes.

Individuals with a criminal record short of a felony conviction, such as an arrest, detention, investigation or misdemeanor conviction, choose to seek expungement.. However, even if you expunge a record, it is still accessible to law enforcement agencies.